Our guest blogger today is Catherine Bryars, a pee-cycling professional and graduate student in the Regional Planning Program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She will present a free talk on Wednesday, May 28 from 7:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. at 204 Long Pond Road in Plymouth, MA as the fourth in our speaker series, Making Waves in Coastal Conservation. As space is limited, please preregister by emailing: dss@goldenrod.org.

Originally from Atlanta, Catherine came up north years ago to attend Amherst College where she majored in Environmental Studies and minored in Latin American Studies. Catherine focused her undergraduate studies on sustainable agriculture and grassroots social movements for environmental justice. In addition to working domestically with farms such as Seeds of Solidarity in Western Massachusetts, Catherine has volunteered with community-based organizations in rural Brazil and Mexico. Her graduate research focuses on the integration of ecological sanitation technologies into regional food systems planning. She currently works with the Rich Earth Institute in Brattleboro, Vermont to support the first community-led project to recycle human urine into agricultural fields in the United States.

It’s odd to me that we never learn in primary school that each of us produces abundant amounts of fertilizer. Specifically, human beings produce about 11 pounds of nitrogen and almost a pound of phosphorus per year. How could we produce these plentiful fertilizer nutrients? In our human waste. In fact, our human urine and feces have a Nitrogen-Phosphorus-Potassium (NPK) fertilizer ratio of about 11:1:2, which can make for some quality soil enrichment! And that’s exactly what many people in our region have begun to do with reclaimed human urine.

It’s odd to me that we never learn in primary school that each of us produces abundant amounts of fertilizer. Specifically, human beings produce about 11 pounds of nitrogen and almost a pound of phosphorus per year. How could we produce these plentiful fertilizer nutrients? In our human waste. In fact, our human urine and feces have a Nitrogen-Phosphorus-Potassium (NPK) fertilizer ratio of about 11:1:2, which can make for some quality soil enrichment! And that’s exactly what many people in our region have begun to do with reclaimed human urine.

You see, human urine contains the vast majority—over 80%—of the nutrients produced in human waste. Human pee is sterile in healthy populations and can be easily sanitized when necessary. This nutrient content of pee is unknown to many, but folks living along the coast of Massachusetts are becoming acutely aware of humans’ nutrient producing capabilities. Beloved bays and estuaries have become polluted and stagnant due to excess nitrogen and many are closed to shell fishing.

Human excreta from septic systems, leaky sewer systems, and decrepit wastewater treatment plants are often to blame for this problem both in saltwater and freshwater. However, innovative technologies are turning this problem into a big opportunity.

Urine solution application by Konrad Scheltema and his son during field trials. Photo by Abe Noe-Hays, Rich Earth Institute.

The Rich Earth Institute in Brattleboro, Vermont is diverting human urine from the wastewater stream, treating it, and then applying it as a fertilizer at family farm sites in southern Vermont. And they aren’t the only ones. These projects, despite the initial “ick factor” for some, demonstrate that regular citizens, farmers, wastewater treatment plant personnel, septic haulers, public health officials and regulators are not only open to this resource reclamation alternative, but can become enthusiastic supporters and begin to feel directly invested.

My own work focuses on the public policy aspect of this topic since I am pursuing a Masters in Regional Planning with a focus on

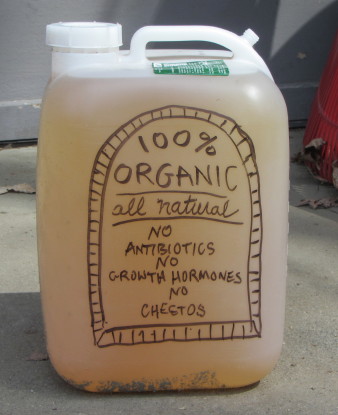

Urine collection techniques range from the do-it-yourself kind to fancy urine diversion toilets. Photo by Abe Noe-Hays, Rich Earth Institute.

alternative sanitation policy. My research has taken me to southern Mexico where similar projects are being implemented in indigenous communities. I have also collaborated with people working in excreta pollution remediation and nutrient recycling in several states of the USA.

For my May 28 presentation I will discuss the pioneering work of the Rich Earth Institute as well as other groups in Western MA and on the Cape who are testing the opportunities and challenges that pee-cycling presents to towns and their citizens. Please join me with your questions and comments on Wednesday, May 28 at 7:30 p.m. for a lively discussion!

Seth True of Best Septic Services pumps out urine from a community urine collection depot for transport to a local farm. Photo by Abe Noe-Hays, Rich Earth Institute.

Please contact dss@goldenrod.org to preregister! Header photo by Abe Noe-Hays, Rich Earth Institute.